Morningstar

Morningstar

Everybody wants that secret to making money in the market. Unfortunately, that secret doesn’t exist.

Financial planning, asset allocation, and investment portfolio management are all based on disciplined principles that, over the long haul, hold up to rigorous examination. The reason for this is that within very strict statistical boundaries, financial assets exhibit very predictable behaviors.

Morningstar

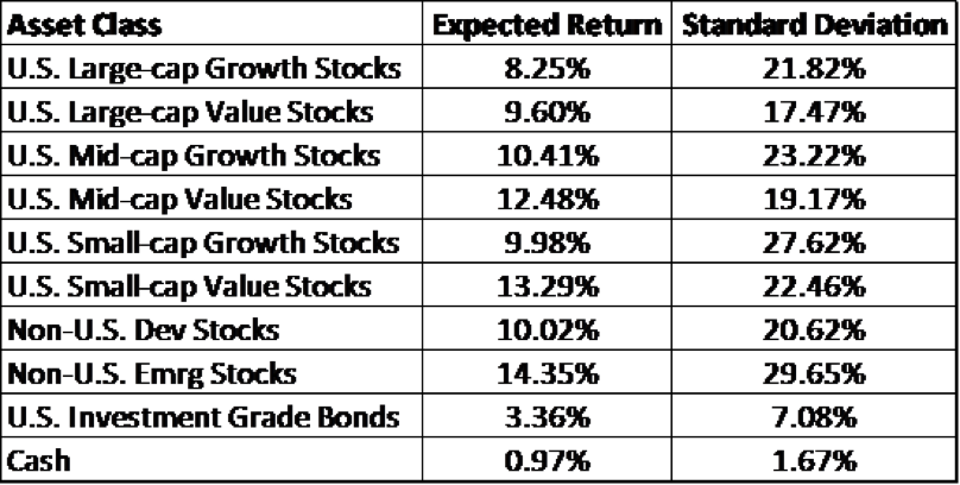

Morningstar(Source: Morningstar)

The table above illustrates how various asset classes have behaved over long periods of time (since 1926 for stocks and since 1970 for bonds). For example, the table shows us that large domestic stocks have appreciated at an average rate of 8.25% for nearly 100 years and presented investors with average volatility (or risk) of about 22% over that same time.

In half of the years for which data was collected to produce the table above, stock prices advanced by more than 8.25%. They went up by less than 8.25% in the other half. And, in some of those years, they actually declined in value. What’s more, in half of the years measured, volatility was actually lower than the 21.82% standard deviation presented above. Unfortunately, in the other half it was higher – sometimes a lot higher!

All of this talk about historical averages and their relation to expected risk and return gets me to the main point. The pesky thing about averages is that the numbers that make them up just aren’t that predictable! Just because we know what the actual return on stocks was in a given previous year doesn’t give us any insight into how they’ll end up in any future year. It’s not like we can simply plug in a number to make the two years average out to 8.25%. Anyone who lived through the 2008 financial crisis knows that!

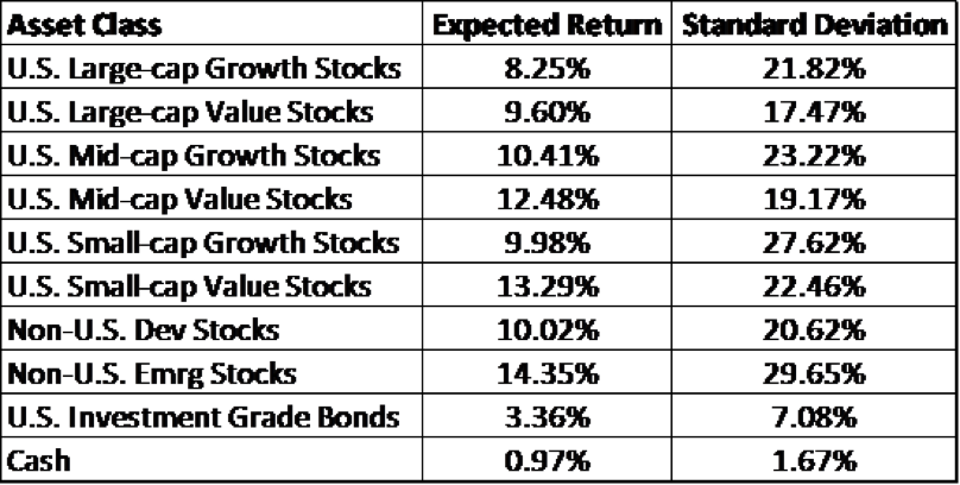

StockCharts.com

StockCharts.com(Chart courtesy of StockCharts.com)

This uncertainty about how stocks are going to behave in any future year is referred to as Sequence of Returns Risk. Over the course of many years stocks may well appreciate at some average expected rate of return. Unfortunately, we can’t predict with any certainty the pattern they’ll exhibit in the future as they bump up and down on their way to that long-term average. This sequence of return risk is especially vexing for newly-retired investors whose financial assumptions are based on those same average expected rates of return.

So, how can investors – especially those who have just retired or who are just about to retire – mitigate sequence of returns risk?

In our view, the main focus should be to compartmentalize the various assets within your portfolio for the purpose of achieving specific investment objectives. Sequence of returns risk is greatest for retirees whose income and spending are derived from (and therefore dependent upon) the performance of their riskiest assets – namely their common stock portfolios. Financing day-to-day living expenses with long-term assets is unwise. Instead, investors are better served by matching the timing and need for income with a suitable investment designed for such purpose.

Investments further down on the risk continuum than equities would be most appropriate in this case. Having a cash buffer is often a necessity for retirees. An ample “rainy-day” fund is imperative. But, that reserve needs to be augmented with funds for regular, ongoing expenses. And, it should be replenished, not from income or gains from a common stock portfolio, but from assets that are specifically designed to produce income.

The careful and judicious use of annuities, may, in certain cases, provide steady income for a set period of time or for the duration of one’s entire life. But that is not the only way that retirees can manage sequence of return risk.

According to Wade Pfau, Ph.D, a professor of Retirement Income in the Financial and Retirement Planning program at The American College of Financial Services, who is considered a leading expert on sequence of returns risk, there are four strategies that investors of retirement age should follow:

- Spend Conservatively

- Maintain Spending Flexibility

- Reduce Volatility

- Buffer Equity Assets

In essence, Pfau suggests that retirees not just live within their means, but that they also keep their spending consistent (on an inflation-adjusted basis) throughout their retirement years. He also suggests that one’s asset allocation can be a very effective way to reduce a portfolio’s overall volatility. To buffer equity assets during a market downturn, Pfau advises that investors should look to some of their other assets as sources of liquidity. These could include the cash value of whole life insurance or the equity in one’s home.

We tend to agree with Pfau’s philosophy. After all, sometimes even the best-laid plans can fall short. Nevertheless, we can’t emphasize enough the value of working with an advisor who is skilled in the disciplines of financial planning and strategic asset allocation. While stock market returns will continue to vary from year to year – and periodic shocks will create episodes where equities hand investors short-term negative returns – we remain practitioners of the science behind the two disciplines.

Investors who are relying on stock market returns to finance their retirement spending are most susceptible to sequence of return risk. That’s why those at or near retirement age would be well advised to do some soul-searching, some planning, and perhaps a little tinkering with their asset mix.

Unpredictable stock market returns – the very essence of sequence of return risk – shouldn’t be a surprise to investors. After all, bumps along the road are a very real component of the long-term historical averages and future expected returns upon which we have all come to rely.